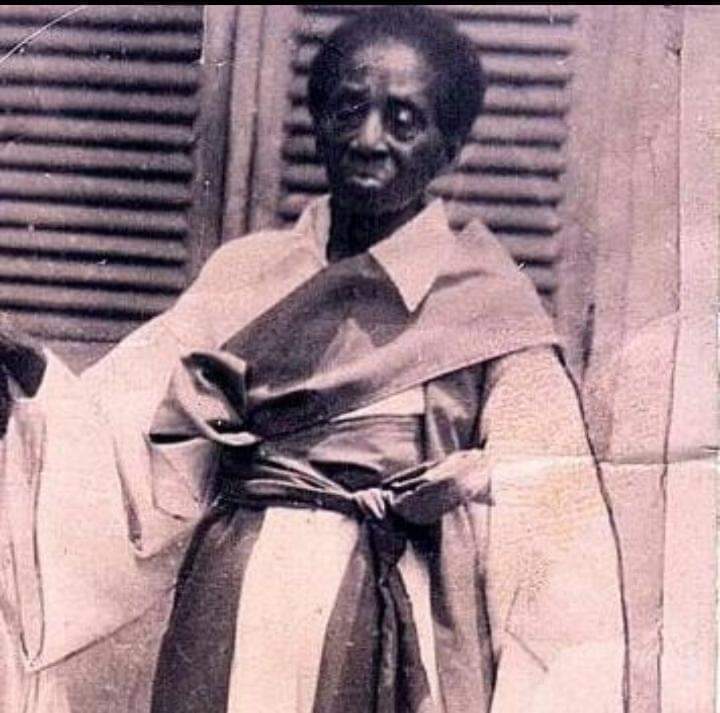

56years ago today, February 4, 1965, Dr. Joseph Boakye Danquah, a Ghanaian politician died in Nsawam

after 13 months in detention without trial under President Kwame Nkrumah’s preventive detention regime. We reproduce his last letter to Kwame Nkrumah before his unfortunate demise.

Dear Dr. Nkrumah,

I am tired of being in prison on preventive detention with no opportunity to make an original or any contribution to the progress and development of the country, and I therefore respectfully write to beg, and appeal to you to make an order for my release and return home. I am anxious to resume my contribution to the progress and development of Ghana in the field of Ghanaian literature (Twi and English), and in Ghana Research (History and Culture), and I am anxious also to establish my wife and children in a home, to develop the education of my children (ten of them) and to restore my parental home at Kibi (Yiadom House) to a respectable dignity, worthy of my late father’s own contribution to the progress of our country.

You will recall that when in 1948 we were arrested by the British Government and sent to the North for detention they treated us as gentlemen, and not as galley slaves, and provided each of us with a furnished bungalow (two or three rooms) with a garden, together with opportunity for reading and writing. In fact, I took with me my typewriter and papers for the purpose, and Ako Adjei also did the same, and there was ample opportunity for correspondence.

Here, at Nsawam, for the four months of my detention up to date (8th January to 9th May 1964), I have not been allowed access to any books and papers, except the Bible, and although I was told in January that my application to write a letter to my wife, Mrs. Elizabeth Danquah, could be considered if I addressed a letter to the Minister of the Interior, through the Director of Prisons, I have not, for over three months, since I wrote to the Minister as directed on the 31st January, 1964, received any reply, not even a common acknowledgement from the Minister as to whether I should be allowed to write to my wife or not. As I had no opportunity to make any financial provision for my wife and children at the time of my arrest, this delay in the Minister’s reply has made it impossible for me to contribute to the progress and maintenance of my wife and also for the education of my children as is my duty to the nation.

Secondly, you will recall that barely a month after our detention in the North in 1948, we were brought down to Accra and released to appear before a Commission of Enquiry set up to investigate the justice or otherwise of our arrest and detention. We duly appeared before the Watson Commission and made history for Gold Coast and Ghana. It resulted in the finding that the Burns Constitution was outmoded at birth, with a recommendation that our country should attain its independence within ten years, and that a Constitutional Committee (the Coussey Committee) should be set-up to lay down the foundations of such independence and the steps to be taken towards its attainment.

In the present case, since I was arrested four months ago, I have not been asked to appear before any Judge, or Committee, or Commission, and, up to now, all I have been told is contained in a sheet of paper entitled “Grounds for Detention” in which I am accused that “in recent months” I have been actively engaged in a plan “to overthrow the Government of Ghana by unlawful means”, and that I have planned thereby “to endanger the security of the State” (the Police and Armed Forces).

As no particulars of any kind were provided in the grounds for detention to indicate how the Government of Ghana came to formulate such a disgraceful charge against me, I spent in the prison here the greater part of January and February 1964 to write a review of the whole of my activities “in recent months” (roughly, from June 1962 to January 1964). This writing was done by way of “Representations” in answer to the charge. The review, in two documents of about 50 pages, has been in the hands of the typists in the office of the Assistant Director of Prisons, Nsawam Prison, since the 16th of February, 1964. The final typing was seen by me on the 17th and 18th April, and I understand they are busy making corrections. As, however, they are a busy people, I cannot expect more than this from them.

I confidently assure you, Sir, that when my representations reach you, it will be realized that my contribution in the said period of “recent months” to the intellectual and cultural achievement of the country was such that what should have been sent to me on January 8, 1964, was not a hostile invasion of my home and family, like enemy territory, together with my arrest and detention, but rather a delegation of Ghanaian civil officials and other dignitaries to offer me the congratulations of the nation and the thanks of the Government for my inestimable and distinguished contribution to the higher achievements of our great nation.

This, however, was not to be, and I find myself locked up at Nsawam Prison in a cell of about six by nine feet, without a writing or reading desk, without a dining table, without a bed, or a chair or any form of seat, and compelled to eat my food squatting on the same floor where two blankets and a cover are spread for me on the hard cement to sleep on, and where a latrine pan (piss pot) without a closet, and a water jug and a cup without a locker, are all assembled in that narrow space for my use like a galley slave.

As aforesaid, I am not allowed to do any reading except the Bible, and I am, on the other hand, required to sleep or keep lying down on the blankets and a small pillow for the whole 24 hours of the day and night except for a short period of about five minutes in the morning to empty and wash out my latrine pan, and of about ten to fifteen minutes at noon to go for a bath. I am occasionally allowed to do a short exercise in the sun say once a week for about half-an hour.

That is all I have been engaged on in four months with any talents, such as I possess, going waste and my health being undermined and my life endangered by various diseases without being allowed to be taken to the Prison Hospital for continuous observation and treatment.

Mr. President will be the first to agree with me that when I talk of my talents and contribution, I do not do so from a spirit of empty boasting, but that the examination of my career as a student in England (1921 to 1927) where I and others established the West African Students Union (W.A.S.U.) and the Gold Coast Students Association, and further, the examination of my career as a politician at home, from 1927 to 1957, when I established the Gold Coast Youth Conference (1927 to 1947), and, together with the late distinguished George Alfred Grant and others, established the United Gold Coast Convention (which sent for you from England in 1947 to come and help us), together with examination of the number and quality of books I have written on Ghana–acts which readily justified my position as foundation member and Fellow of the Ghana Academy of Sciences–fully entitle me to say that so long as there is life in me and my energy remains unimpaired, I can yet add a few chapters to the richness of our history, not in particular as what the Watson Commission called “the doyen” of our politics, but in the field of pure literature and pure knowledge for which the Academy of Sciences exists under your direction and presidency.

Osagyefo will, I am sure, readily recall that I wrote my first book, The Akan Laws and Customs, at a time when I was a young clerk (Tribunal Registrar) at Kibi and when I was hardly 25 years of age and had not seen the inside of a College or University. That book is now a classic and has in recent years been quoted with approval by the Privy Council. I have myself no doubt that I have many more years of useful service in me for the nation, and I am anxious to let the nation have use of it.

As for politics, I assure you, Sir, that I have had my fill of it. I feel that the time has amply arrived when I should leave that area of our life to the younger folks coming after us to occupy their talents and strive as much as they can for its tricky laurels. As you may have noticed, from June 1962 to January 1964, after my release from the 1961 detention, I did not attend or summon a single political meeting or committee. The manuscript of my book The Ghanaian Establishment, which appears to have caused a furore when a copy was seen in the Post Office, or was taken from my bedroom desk by the Ghana Police, is really a collection of matters which are already public property, namely, my public lectures, and my letters to you and certain Government officers, such as the Chief Justice and the Speaker, and also a reproduction, with a short comment by me of your two famous radio talks on the decline and degeneracy of our morals in certain quarters during the last few years.

With regard to this manuscript, I feel very strongly, Sir, that if there was anything about its contents which was objectionable to you, you could have sent for me for a discussion and I would readily have apologized and withdrawn the intended publication or the portion of it objected to by you.

However, I am now left in a prison cell at the Special Block at the Nsawam Prison reserved for “dangerous criminals”, and I am being thereby effectively prevented from making any original contribution to the intellectual and cultural progress of our country, in particular my work on the Ghana hypothesis of our Gold Coast origin is being held up, and the Universities and the students and the scholars of our country are being deprived of the materials which by 36 years of research has made me one of our country’s specialists, a subject which you yourself referred to last year in your speech at the Ghana University that “our friend Danquah has also written some books on Africa”–or words to that effect.

When in this connection, I read the second paragraph of the grounds for my detention and gathered that I am being punished by imprisonment to prevent me from taking any part in the country’s life, not for what I have done at present but for what I may do, or not do, “in the future”. I was completely astonished that in taking that decision Government did not balance my distinguished record at my age 68 against the possibility of an offence entirely foreign to me, and to my career and my way of thinking.

The curious text of the second paragraph of the grounds for detention reads:

“Your detention is necessary in order to prevent you from acting in future in a manner prejudicial to the security of the State”.

This is punishment for a crime not yet committed, and Mr. President will, I am sure, be the first to condemn it when its full implications seize his soul and his spirit in a vision of God.

I was told by the Army Officer who arrested me at my residence, on January 8 that my wife and children and other residents should leave the house within six hours and I noticed that the Arm Officers commenced a search into my papers. I was not told for what purpose the search was being made. If perchance they were looking for evidence of any crime against the State anyone who knows me as a person brought up in the Yao Boakye tradition of respect for authority (SUSU BIRIBI) would assure you Sir, that if a search was made for felonious or treasonable matter in my house and papers, nothing of the kind would ever be found.

However, since the search was commenced in my house by the Army four months ago, no one has approached me on any matter found in that search. I can assure you, Sir that many as are my papers and books, crimes against the State are not to be found in me.

In the circumstances, I respectfully assure you, Sir that it would be more profitable for the nation and people for me to be released and allowed to go on with my intellectual and cultural contribution to the progress of the State. When last year you sent me a complimentary copy of your book, Africa Must Unite, actually autographed with your own signature, I was delighted to note this further evidence of friendship and esteem, and I was happy to note also in the Messenger’s Receipt Book that the other distinguished Ghanaian to whom an autographed copy of your book was likewise sent, was the late Dr. Burghardt du Bois.

In my letter of thanks, I mentioned that I had earlier bought a copy of the book and had wished to meet you to discuss the matter before your departure to the African Summit Conference in Addis Ababa. This, however, could not be arranged by Mr. Okoh, the Cabinet Secretary, and therefore, up to now, you have not obtained my views on this question of African unity. I do hope that when I come out we shall have an opportunity of discussion on how best a United Nations of Africa or an African United States could be brought about around a central unificatory and attractive idea.

I may be permitted to recall here that when in the earlier years I used to speak of a United Gold Coast becoming independent, my old friend Colonel Bamford, Commissioner of Police, used to jeer at me saying that so long as we had separated tribes the idea of a United Gold Coast could not be realized. When, however later on he heard of my theory of a common origin of Gold Coast tribes from ancient Ghana, he took serious notice of my activities by reason of the attractive unificatory idea of Ghana.

In regard to Africa, I should mention that the term “Africa” itself cannot be very helpful. It, like “the Gold Coast”, is a colonial term. It was the Roman name for Libya (“an ear of corn”). Africa as a name is not found in the most ancient books, not in the Bible, nor even in Herodotus. On the other hand, Ethiopia is found in the Bible, but not in the older authorities, such as Genesis, chapter 10, where it is not mentioned at all in the Table of Nations where Egypt (Mizraim) and Ham and Cush and Seba and Sheba are mentioned. Ethiopia is mentioned in Herodotus, but it turns out to be a Greek colonial term for Cush (Tush), the Greeks having coined the term in place of the Egyptian term for Cush, “Ethaush”, because the Greeks could not adapt themselves to ‘sh’, hence Aethiops. Today, Abyssinia has so thoroughly exploited the Ethiopian idea that I hardly think it may be any longer attractive for a unificatory concept to embrace all of Africa.

The question that is left is this: what is there in this great “Question Mark” of a Continent which had always been responsive to the needs of the world ancient and modern? Why did God take Abraham and his father, Terah, from Ur of the Chaldees and from Haran to promise Abraham and his seed the land of Canaan but He, the Almighty God, deliberately planted Abraham’s seed, Jacob or Israel, through the instrumentality of Jacob’s son, Joseph, in Africa, for 400 years before He called upon Moses to uproot them from Egypt into Canaan? Again, what did God find in Africa to have got the Angel at Bethlehem to advise Joseph and Mary to take the child Jesus into Africa from the threat of death by King Herod?

Why did not the Angel of the Lord advise Joseph to take Jesus into the East where the three Kings had come from with presents to the Baby Jesus, or why did not the Angel advise Joseph to take the child Jesus to Europe, say to Greece or Rome, countries which were at the time the imperial and cultural rulers of the whole of Canaan?

Or to come to more worldly affairs, why did Christopher Columbus visit Elmina in Africa (Gold Coast) before going West to discover the New World, America? It would seem, indeed, that the great discoveries of the fifteenth century, led by Prince Henry the Navigator, both of the Western World and the Far East, must have been inspired by Africa as the pivot and question mark of the universe.

These are some of the ideas to be explored on the Africa question to find out the particular field or fields in which Africa is responsive to the needs of the universe, and thereby to discover an attractive unificatory idea for all Africa to come together around that idea, such an idea, that is to say, as would attract countries like South Africa to join the African union without compulsion, such an idea as would make the great leaders of the world look up to the leader of the new United Africa as a dynamic centre for indispensable consultation.

I do hope that when I come back home we can work out a solution of the Africa idea under the auspices of the Ghana Academy of Sciences or of the Institute of African Studies at the University of Ghana.

I end as I began. I am tired of being kept in prison kicking my heels, and doing nothing worthwhile for the country of my birth and love, and for the great continent of Africa which was the first to give the entire world a real taste of civilization. My labours in African research and Ghana history are well known to you and to many others. In fact, Professor Hodgkin of the Institute of African Studies has asked me to write my biography for the benefit of the country, but, of course, it is impossible for me to comply with his request if I am kept in prison.

My plea and my prayer to you, Osagyefo, is that, I be released to return home for the following specific purposes:

(1) To pursue my vocation for creative work in Ghana literature;

(2) To pursue my vocation for research into Ghana history and culture;

(3) To pursue a home for my wife and children and to promote the education of my children as befits their talents;

(4) To restore my parental home at Kibi to a respectable dignity for use of the younger and older members of the family;

(5) To pursue social and cultural life in Church and State; and

(6) To practice my profession as a lawyer to obtain the wherewithal for the pursuit and promotion of the above interests.

I earnestly appeal to you in the blessed name of God, of Ghana and of George Alfred Grant and of all the great ones of our glorious past as well as the unborn pioneers and guardians of our treasured national liberties and freedoms, to have regard to my national record in the past as a basis for computation of my future activities, and to balance that record against my detention in prison where I cannot lift a finger to add to the nation’s achievements.

For instance, at the present moment, I have three major works out in the world for publication, but I do not know for certain where they are to be found. Assuredly, it is only when I am free at home that I can take steps to retrieve the manuscripts and secure publication.

These are:-

(1) The Ghana Doctrine of Man–Research into the Dual Family System of the Akan People (Ntoro and Abusua) undertake with the assistance of Sir Alan Burns’ Government. (Your Government Cabinet Secretary, Mr. D. A. Chapman, has an earlier copy of the manuscript. The definitive copy is with a friend at U.N.E.S.C.O., Paris.)

(2) The Elements of Ghana Culture.–This is a collection of my lectures and essays on our origin from ancient Ghana. Last year the manuscript was in possession of a friend at Reed College, Oregon, in the United States, but I do not know for certain where it is today.

(3) Sacred Days in Ghana.–This contains additional and conclusive proof of our cultural achievement, in particular the Ghana Calendar of a planetary week of seven days, which confirms my theory of our ancient and undoubted membership of an earlier civilization. This manuscript, too, was in the hands of the Professor of Sociology at Reed College, Oregon, U.S.A., up to last year, but I do not know for certain where it is today.

I trust you will accept this appeal for my release from detention in the spirit of utmost confidence and cordiality in which it is written, and I look forward to my early release from prison with the greatest possible faith, expectation and confidence.

Believe me to be,

Osagyefo,

Yours Very Sincerely and Respectfully

(sgd.) J. B. DANQUAH