THE HISTORY OF FANTES

The Fante people lived around mankessim. By the 13th and 14th century Borbor Mfantse have spread to most parts of what is today Central Region of Ghana. Gomoa, Nkusukum, Ekumfi were the early migrators from Mankessim. The Fantse language is part of the Kwa group, and Inheritance and succession to public office are determined mostly by matrilineal descent.

According to oral tradition, the Fantes arrived in their present habitat from the north by the 13th century. Mfantse (Fante) according A. B Crayner derives from when the Borbor group arrived at Mankessim. The place was inhabited by the Etsi people (Guan) and the leader of the Borbor group asked his people to adopt the language of the Etsi people as a tactics to conquer them. Which translates to mo “mfa – etsi” kasa. Therefore, the Fantse language is a combination of Esti, Bono, and later some corrupted European words (Portuguese, Swedish, Dutch and British).

In the early 18th century, the Fantes formed a confederation, primarily as a means of protection against Ashanti incursions from the interior. Several Fante-Ashanti wars followed. The Fantes were aided by the British, who, however, destroyed the strong Fante confederation established between 1868 and 1872, believing it as a threat to their hegemony on the coast. In 1874 a joint Fante-British army defeated the Ashanti, and in the same year the Fante Confederacy became part of the British Gold Coast colony.

Origin

The Fante people claim to have separated from the Bono, another Akan people, around 1250 AD. The Fante left their Bono brethren at Krako, present day Techiman in the Bono East Region of Ghana, and became their own distinct Akan group. The Fante people were led by three great warriors known as Obunumankoma, Odapagyan and Oson (the whale, eagle and elephant respectively). According to tradition, Obunumankoma and Odapagyan died on this exodus and were embalmed and carried the rest of the way.

Founding

Oson led the people to what would become known as Mankessim in 1252. Legend has it that the Fante’s chief fetish priest, Komfo Amona planted a spear in the ground on arrival at the settlement. The spear is called the Akyin-Enyim, meaning “in front of god.” The place became the meeting ground for Fante elders and the head fetish priest when discussing important matter for the kingdom and even for all Fante people. The first Omanhene (king) of Mankessim was installed here, and later kingmakers would go to the site for consultation. According to the Fante, the spear cannot be removed by mortal hands.

The Fante first arrived at their initial settlement called Adoakyir which was named by its existing inhabitants, which the Fante called “Etsi-fue-yifo” meaning people with bushy hair. The Fante conquered the people and renamed the settlement Oman-kesemu meaning big town. The name exists today as Mankessim. The Fante settled on the land as their first independent kingdom and buried Obunumakankoma and Odapagyan in a sacred grove called Nana-nom-pow. Komfo Amona also planted the limb of a tree he had brought from the Akan homeland in Krako to see if a place was good for settlement. The day after the priest put the limb in the ground, the people found the plant budding. The tree was named Ebisa-dua or consulting tree and is one of the most important shrines in Mankessim today.

Organization

The Fante quickly organised themselves into military groups or companies called asafo to fend off non-Akan groups in the vicinity as well as separate Akan groups, most notably the Asante in later centuries. Traditional states of the Fante sub-groups; Ekumfi, Abora, Enyan, Nkusukum and Gomoa were the first to settle and migrate out of Mankessim. Other Fante States like Kurenstir, Ajumako, Agona, Akatakyi, Abeadze, Breman, Asebu, Oguaa, Komenda, Anomabo and Edina joined.

The Asante threat

In the early 19th century, the Asante began expanding their control over Ghana which led to the exodus of many people to the coast. Fante communities outside of Mankessim became constant targets of the Asante and decided to unite on occasion to fight off the Asante. In 1811, the Fante again went to war with the Asante losing again in open battle, but forcing a withdrawal by using guerrilla tactics. In 1844, the Fante put themselves under British protection, but were guaranteed self-governing however, the British and Dutch on the coast did little to recognize Fante sovereignty.

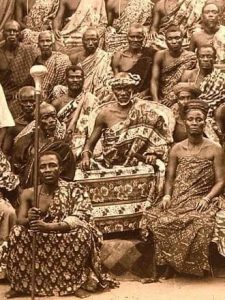

Head of the Confederacy

Finally, in 1868, the Fante formed a confederacy of their own after the British decided not to back them against further Asante aggression towards the coast. The Fante met in Mankessim and elected the kingdom’s Omanhene as Brenyi over the Fante Confederacy. In 1871, the seven Fante kingdoms and 20 chiefdoms signed the Constitution of Mankessim formalizing their alliance. (The Fante Confederacy consisted of Efutu, Assin, Awutu, Wassa, Ahanta, Twifo and Denkyira who were all Fante allies)

Omanhene Kwasi Edo led the confederacy all of its short existence acquiring the lands of neighboring Asebu, Cabesterra and Agona kingdoms. They also formed a viable resistance to the Asante juggernaut. Mankessim, through the confederacy, monopolized trade on the coast and became a force to reckon with by the Asante, British and Dutch.

The early successes of the confederacy were short-lived and a protracted war with the Dutch, backers of the Asante Confederacy left them in ruins. In 1874, the British proclaimed the entire coast of Ghana (then known as the Gold Coast) a protectorate of the crown. In the same year, the Fante Confederacy was dissolved by the British who saw it as a threat to their colony.

The Asafo warrior clans

The word `Asafo’ is derived from ‘sa’ (meaning war) and ‘fo’ (meaning people). Warrior groups are active throughout the Akan area, but it is the Fante tribe which inhabits the coastal region of Ghana, that developed a sophisticated and expressive community with a social and political organization based on martial principles, and elaborates traditions of visual art.

It is certain that the local organization of warriors into units of fighting men was an established practice well before the arrival of Europeans. Nevertheless, the influence on – and the manipulation of – these groups to suit the trading and colonial ambitions of the foreigners created many of the qualities of the Fante Asafo that continue to this day.

The situation throughout the Fante region is fraught with political complexities, for there are twenty-four traditional states along a 100 – mile stretch of the Atlantic coast, and each state is independently ruled by a paramount chief or ‘omanhen’, supported by elders and a hierarchy of divisional, town and village chiefs. In any one state there may be from two to fourteen Asafo companies, with as many as seven active companies in a single town.

By exploiting these divisions, the Europeans could `divide and rule’ and ensure that their control of the coast went unchallenged. At the same time, by organizing the Asafo warriors into efficient military units, they could bring together an army for a quick reaction to any threat from the interior. The enemy was, more often than not, the Ashanti kingdom, a traditional opponent of the Fante. The primary function of the Asafo, as we have seen, was defence of the state, nevertheless, the companies are key players in a balance-of- power struggle – typical of the many that exist in communities the world over – between the military and civilian groups within government. Although the Asafo are subordinate to their chiefs and paramount chief, they are intimately involved in the selection of the chief and are responsible for his crowning or ‘enstoolment’. As long as the chief has the support of the people – as represented by the Asafo – he has the authority accorded to him by tradition; the prerogative to appoint and remove chiefs remains with the people. Asafo elders also serve as advisers to the chief.

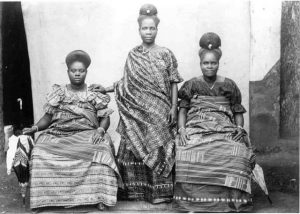

While Fante chieftaincy is aristocratic and matrilineal – the chief tracing his descent through females back to the founders of the community – the Asafo are patrilineal and democratic, every child, male or female, automatically enters his father’s company, and membership is open to all classes, from stool holders to fishermen.

The use of flags in the Asafos

The installation of a new Asafo captain is the principal motivation for the creation of a flag. It is the responsibility of the incumbent to commission and pay for the ensign, which then becomes the collective property of his company. The choice of design is his, albeit partly limited to mimicking the examples established by precedent to be the artistic property of the company. The personalizing of flags in memory of the commissioning officer is now a common occurrence.

The display of Asafo flags is associated with the social activities of the company and the town as a whole. For the town the major event of the year is the Akwambo (path-clearing) festival. This is a time of unity, of renewing allegiances and friendships and of the homecoming of family members especially for the celebrations. Paths are cleared to shrines of the gods, often by the river, and as this is a large-scale event it is the time of the presentation of new Asafo leaders, such as supi or asafohen. Bearing their flags, the Asafo companies parade through the streets, to the river, to the town shrines and past the houses of the chiefs to demonstrate their allegiances.

At these festivals the companies of a town proudly and aggressively defend the right to parade specific and exclusive colours, cloth patterns, emblems and motifs on their art forms. The violation by mimicry of a company’s artistic property, established by precedent and since 1859 by local law, is seen as an act of open aggression. The flags are also shown at other Asafo events, including the funeral of a company member and the commissioning of a new or remodelled shrine, or on an important anniversary of its original construction. Town, regional and national events, such as the enstoolment of chiefs, the annual Yam Festival and state holidays, are all celebrated with a show of Asafo flags.

At these social events the flags are displayed in a variety of ways. The flagpoles of the posubans, the shrines of each company, proudly carry the flags aloft and the houses of Asafo members adjacent to the shrine, as well as the shrine itself, are decked with strings of colourful colonial and Ghanaian ensigns. Flags are carried in processions and, most dynamically, there is a spectacular display of elaborate dancing with the flag by specially trained Asafo officers, the ‘frankakitsanyi’.”

In 1853, Cruickshank noted that each company has a distinctive flag; for a company member, ‘the honour of his flag is the first consideration’. He also comments that some flags are specifically designed as challenges or insults to rival companies.

These visual insults and provocations often resulted in fatal inter- company clashes. An image of one company catching their enemies in a dragnet brandished by one company at a festival in July 1991 nearly caused a riot! Earlier incidents such as these led to the strict control of flag imagery. At Cape Coast, beginning in the 1860s, all companies were ordered to submit their flags to the Colonial Governor for his approval and to register the approved designs and colours with his secretary. The display of unregistered flags was punishable by law. Even today a new flag must be approved by the paramount chief, the general of the combined companies and the Asafo elders, then paraded before all the other companies in the area to make sure that no one is offended.